Summary: We made an unscheduled visit to the Cadillac Motel, Tent City, and Lee Manor to distribute warm clothes to those in need. While at Tent City, we were given unprecedented access to areas we had been unaware of until now. We returned to our regularly scheduled time on Saturday, November 28th, and distributed even more, including Greentree Apartments.

Read Time: Approximately 10 minutes.

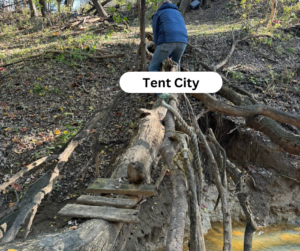

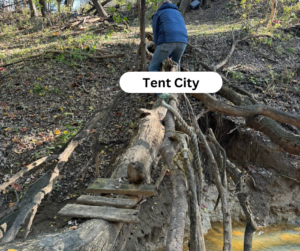

Last month in October, I was on cloud nine after being given what I thought at the time was full access to Tent City, which was and still is considered a rare privilege. We were invited into their homes. I was satisfied that I had seen it all. I was so wrong. What happened on Saturday, November 16th, was certainly one of the highlights of my life thus far. But before we go there, let’s start at the beginning, and I’ll take you through the truly extraordinary day.

We show up at the Cadillac Motel on the last Saturday of every month. Because this was the middle of the month, people were not expecting us and were not waiting for us upon our arrival as usual. Due to the temperature dipping down the forties at night, we decided to deploy as many totes containing coats and blankets as we could transport. This is why we’ve been collecting these warm clothes since we ran out in March 2024.

It wasn’t long before there was a line of people—a whole bunch of people. Everyone stood in line and respectfully took what they needed in proportion to their family size. We intentionally did not include food and hygiene items to maximize the coats and blankets we could provide. And guess who shows up out of nowhere? River Tree Church. And they’ve brought hot breakfast, coffee, and fruit to go. Unknowingly, until now, we realized that this was Eaton Memorial’s Saturday to provide a hot lunch further up the street. Repeatedly, God demonstrates how He can use different people and put them on the same path to serve his purpose. Everyone got a coat and blanket and their choice of warm food. Or one of each. I didn’t see anyone getting turned away over food.

I love handing out food. It’s heartbreaking to watch someone so hungry that they eat right out of the food bag, but it’s also rewarding that they get to eat. This time of year, though, is my favorite. Nothing tops the experience of watching someone shivering in the cold put on a warm coat right in front of you.

We had some new volunteers arrive. Among them were a husband-and-wife team and a friend they brought along. They call him Cherokee. I was told that he was close to the community, and I quickly noticed how he conversed with many of the people, some of whom I had not seen before. Cherokee knocked on all the doors on one side of the property, and I took the other. We had a huge turnout.

We loaded up and headed to Tent City. We were unloading our tables and totes when I suddenly realized that Cherokee was about to find everyone who lived there and inform them of our arrival. I can’t tell you how that reached my awareness, but that part of me said, “You need to go with him.” I asked, and Cherokee patiently waited for me while I changed out of my shoes into my hiking boots. This would ultimately be the only moment Cherokee would show me mercy. More on that later.

Cherokee, his friend, who we will call “Larry,” and I begin walking down the trail toward Tent City. Cherokee is walking way ahead, which will turn out to be how he prefers it, and Larry and I converse amongst ourselves, following behind. While answering Larry’s questions, I told him what I thought would happen and what a rare privilege it would be to be invited back into camp.

The three of us crossed the camp’s threshold, down the embankment, and into what I had convinced myself was “Tent City.” Cherokee approaches every home and metaphorically knocks on every door. Only in this case, there’s no actual door but a boundary around every “house.” These boundaries can be decorative fences constructed of driftwood, chicken wire, or walls of tarps surrounding their living area for privacy. We find some people at home, some not.

Cherokee walks to what I thought would be the southern edge of Tent City and shows us a ravine that branches off from a body of water with a giant plastic cube floating in it. He explains how one would get on the cube and pull themselves across the water to the other side with a rope to reach the different camps. It’s probably fifteen feet across, and I am told that the water would have a depth greater than the height of a man. “Cool,” I thought.

Then Cherokee begins to plow North on a trail I had not noticed before. Larry and I follow Cherokee from a distance behind, not because we’re uninterested but because Cherokee is flat-moving. Cherokee has spoken little. He is mostly silent, and I’m getting the impression that’s just who he is. Continuing to talk among ourselves, Larry starts verbalizing the right questions as he absorbs the scenery around him. “Why do they live here when there are shelters?” “Why doesn’t our local government do anything to help?” “What are they going to do for heat?” All good questions. It occurred to me that I once asked the same questions, but since then, I have decided to stop chasing after the answers that did not exist and be content with helping.

Having done this for a few years, I’ve seen many people with huge ambitions come and go. I get it. People have good intentions. Larry is talking about constructing a large tent, providing heat and a grill on which he can cook food for the residents, getting to know them, and writing a book about their lives. It’s easy to say, but it’s a different matter to see it through.

We approach several little campsites. These homes are nothing more than pup tents. There are no fences to denote boundaries, outside living areas, or amenities. Throughout the day, I observed that for every resident we came across, Cherokee called them by name. Additionally, I noticed that he made a sound like a bird before approaching each home. This sound alerts the resident that someone friendly is approaching.

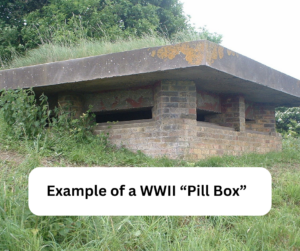

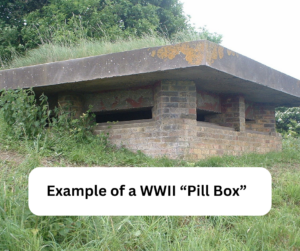

The trail ended at a home that was more of a fortress. A concrete ditch ran down the embankment toward a body of water, trickling with rainwater. A wooden walkway spanned across, leading up to a home constructed with tarps perched at the top of a hill looking out amongst the smaller tents. I suspect the walkway could be retracted, making it a slight deterrent. With the back end of the home against a steep, seemingly unclimbable embankment and the front view reminiscent of a WWII pill box, you might call it a strategic location. We are warmly greeted by a man I have become acquainted with over time, who lived there. And his dog, who I think was said to be eleven years old. The man who had traveled there with Cherokee and I, Larry, knew the resident from when they were young. I gave Larry the whole “God puts people in our path for a reason” speech and suggested that they walk up together to where our totes were set up and get caught up, which they did, leaving Cherokee and me alone. And then it begins.

I follow Cherokee to the ravine. We climb down the embankment, and he pulls the rope attached to the plastic cube to bring it to where we stand at the water’s edge. “Hold up”, I say to myself. Am I about to climb aboard a wet, slippery plastic cube and pull myself across to the other side with nothing to hold onto but a piece of twine? As Cherokee pulls himself across the water, I try to think of everything that could go wrong. I can swim, but that’s not the concern. The water is cold; when I slip off and get wet, it will take a while to return to where the rest of our team was. Hypothermia crossed my mind. My phone will get wet, which is okay; it’s just a phone. But that meant if something went wrong, my location would be unable to be tracked. If my wife were there, she would go ballistic. But I told myself that if this guy was going to take me seriously, I had better show myself to be willing to do and go wherever he did. So, I climbed upon the bobbing cube floating in the water and pulled myself across to the other side—a point beyond return. I’m told this design is a deterrent to law enforcement or other entities whose job it might be to displace those living there. I’d say it works.

Let me stop here for just a minute. I know this will be hard to believe, as it is for me. But after this point in our journey, I’m missing parts of my timeline. My wife says it’s because I was on such an emotional high, which is true. It was surreal; I was in a different world. And perhaps there are parts that I don’t want to remember. I feel like I have been liberal up to this point with my description of what it looks like inside this foreign place, but that’s got to end here. Given the incomprehensible impoverishment, I can’t share the private living experience of each of these people. It feels wrong. Would you want someone reporting on your living conditions, especially if they were not something to brag about? For this reason, I have set a few rules for myself when visiting areas like this. The first and most important is to be mindful of where my eyes travel. This means that I intentionally try not to look at anything that might be personal. Like their sleeping area.

I will say this. If you had a heart, you’d feel like it’s been ripped out. It’s best if you think of Tent City as being like Owensboro. You have subdivisions. I was hoping you could think of the part of Tent City I had been exposed to up until now as if it were Stone Gate or Lake Forrest. These are well-established, nice parts of town for those who don’t know. Having crossed the ravine, it’s quick to recognize that this is the polar opposite. I remember bits and pieces. A person is lying on the ground with a tethered tarp stretched out over them at an angle to allow rain to run off. Or structures that, upon approaching from a distance, were in such bad shape I would have thought that surely there would be nobody there. But there is. And then, in the middle of it all, there would be the occasional well-established home, just like in your neighborhood.

There is one haunting image I can’t get out of my head. I didn’t mean to, but I looked into the eyes of a young woman whose skin stretched out across protruding cheekbones on her face. The skin was pale—dark brown bags under her eyes. Malnourishment. It hurts to be standing there. It hurts because I am outside of my element. I have grown accustomed to seeing people suffer and being in a position where I could do “something.” Not much, but a bag of food, a blanket, or a coat. But I can’t. I stand there in silence.

Cherokee is about six feet tall. And he walks like his legs are ten feet tall. He’s traveling up and down these trails at an unbelievable pace, and it’s all I can do to keep up with him physically. He is at least ten feet before me at any given point. I thought I would either keep up or be left behind. Which, in a way, I deserved, I thought. He has little to say to me. As we visit the different homes, I stay silent and keep my head down. I wasn’t afraid, but I did not want the residents to feel like I was looking at them. After all, I am the outsider. I am the one outside of my element.

We cross two more ravines by precariously balancing ourselves on large limbs that had either fallen or intentionally placed to span the two sides. One of the dead limbs cracked and creaked as I belly-crawled across. “My wife is going to kill me if this breaks,” I thought to myself. The height was undoubtedly enough to fracture a bone or two. Sometimes, the trail completely disappears, and somehow, Cherokee knows precisely where he is going through the brush, and suddenly, a trail reappears, and away we go. Full throttle. There is no way I could find myself around.

We’re coming around a bend. There’s a nice home perched at the top of the hill. I’m slightly discouraged that none of the residents that Cherokee has invited to take advantage of what we were offering seem to be acting upon it. So, I took it upon myself to break the silence and tell the two men observing our movement that provisioning was available for them where our vehicles were parked. One of the men asked me where this was located. I started to point in that direction and then realized I didn’t know where I was. A part of the landscape has remained in view the whole time that I can use as a point of reference, but that’s all I know. I look at the man with what must have been a confused look. He must have thought, “Well if you don’t know where you’re at…” I decided to remain silent.

Cherokee indicates that he is satisfied every door has been knocked on, and we head back. If I didn’t know any better, I have earned some respect, as he begins to walk aside from me but remains slightly ahead. He begins to talk. His voice is calming and soft. I only wish I could remember it all. He’s talking about the different names of the neighborhoods we visited and how each has various social and economic attributes. I’m out of breath and beginning to struggle to keep up. I listen attentively and answer with the occasional “Yes, sir.”

He tells me to be mindful of how I treat “his people,” that I might be speaking to an angel and not realize it, and that all of them are children of God. Wow. He doesn’t know, but that’s something that Ms. Patty would have said almost verbatim. Ms. Patty was the one who got us started in this outreach in the first place. She lived and worked at the Cadillac Motel and slowly acclimated my wife and me to this world and “her people.” Patty was homeless herself once. She passed in August 2023.

We’re walking (or slowly running if you’re me) back past an area we had visited on the way in, where a resident continues to fish. Of course, Cherokee knows the man’s name and confirms with him where the best exit is. The man gives us directions, and we trek up a steep concrete ramp to ground level. The ramp is overgrown, leading to an abandoned concrete pad. I’m unsure what that was used for, but it’s evident that it has been abandoned for decades.

We reach the top of the hill and are faced with a fence. Far in the distance, I can see our vehicles, tables, and totes. About twenty-five yards from where we are standing, there is a gate that we could have easily belly-rolled under. I say, “Hey, there we are; we can just slip under the fence.” Without missing a beat, Cherokee says, “You can go that way if you want. I’m going this way.” He’s determined to go the way the man directed us to. He turns and walks away. There’s probably a good reason for this, and proceed to follow. We approach the hole cut in the chain link fence that we were told of. Cherokee stoops down and struggles to fit his tall stature through the small opening. I made it easy on myself and crawled on my hands and knees through the mud. Once on the other side, I noticed for the first time that the back of Cherokee’s shirt was soaked with sweat. Going ninety miles an hour for five miles also took its toll on him. I catch up to him once again and walk beside him. I thanked him again and told him that this had been one of the most extraordinary things I had done.

Too often, the right path is difficult and leads you to the same destination as if you had taken the easy route. Perhaps Cherokee did not know why he was told to go that way instead of the easier choice, but the guy with the fishing pole knew. Maybe the property owner to who the gate belonged was not receptive to people crawling under it.

The Safer Kentucky Act, which went into effect on July 15, 2024, makes sleeping or camping in public areas, such as Tent City, illegal. The law creates a new offense called “unlawful camping” that can result in arrest and fines. Assisting those individuals is considered to be aiding and abetting, which is a legal doctrine that refers to the act of helping or encouraging someone to commit a crime. The person who aids and abets is generally held to the same degree of criminal liability as the person who commits the crime. We ask that you please not attempt to locate or visit Tent City.

We went back, as always, on the last Saturday of every month. Which was November 30th. I was very thankful that Cherokee, who was open to accepting our invitation to join us, did not ask me to go with him to find all of his people. Not because I didn’t want to. I just couldn’t. I was delighted to see three people we had not seen before from the other neighborhoods at Tent City that we were previously unaware of, which is what we were after. It takes time to develop relationships with people shunned by the world you and I live in. It’s taken us years to get to where we are now. I have read on social media that people report visiting Tent City frequently without any indication that they’ve put forth the effort to develop relationships prior to doing so. If you can hit the fast lane, get to where you need to go and bypass all the formalities, then I applaud that. We prefer the slow and steady approach.

We also visited the Cadillac Motel, Lee Manor, and Greenbriar Apartments on this same Saturday. Thanks to the generous people who donated and our incredible volunteers who showed up no matter what, we distributed over thirty totes of coats, blankets, socks, shoes, hats, gloves, and scarves. About three hundred food bags that contain one protein, such as Vienna Sausages, a tuna pack, or a can of beanie weenies, one package of peanut butter crackers, a fruit cup or apple sauce, one container of peanut butter, one packet of oatmeal, a breakfast bar and a treat, such as a Little Debbie snack.

In closing, I’d like to mention our volunteers. Again, God has placed specific people in our path for a reason and purpose. Tom and Karen Bristow from Ridgewood Baptist usually bring willing participants with them. Tom is a drummer and knows how to pack a van. Stephanie and Kevin Johnson are always there, doing whatever it takes. We had many new volunteers, including a young couple, a welcoming contrast to the rest of us old folk. I feel like our volunteers are a lot like us in that they benefit greatly by having the privilege to love the segment of society that nobody else wants anything to do with.

All of the real names used here were with permission (including Cherokee). Otherwise, the names have been changed. To protect the identity of those photographed, they have been blurred intentionally unless consent was given before publishing.

The Safer Kentucky Act, which went into effect on July 15, 2024, makes sleeping or camping in public areas illegal, including on sidewalks, roadsides, under bridges, or in parks, parking lots, garages, or doorways. The law creates a new offense called “unlawful camping” that can result in arrest and fines. Assisting those individuals is considered to be aiding and abetting, which is a legal doctrine that refers to the act of helping or encouraging someone to commit a crime. The person who aids and abets is generally held to the same degree of criminal liability as the person who commits the crime. We ask that you please not attempt to locate or visit Tent City.

Great team!!! Ty for helping our neighborhoods!!!

How can I be a part of this. I would love to volunteer and help in any way possible. Thank you. My name is Brandi Oberst

2703142811

Thanks for doing this work. Keep it up!